“Qualities of a good job would be the obvious, salary and maybe benefits…”

“A chance for advancement, good working relationships with peers and something you have a passion“…Uses a variety of my skillset, gives me room for failure, gives me room to grow, gives me room to laugh, gives me room to create and to be recognized.”

“It has to be motivating. It has to be flexible, to allow me to do what I need to do.” *

While we are officially in the longest economic expansion in United States history and unemployment is at a decades-long low, we still have a strong sense that too many working people are struggling. Every day we see news of rising inequality between people trying to make ends meet and the wealthiest few. People are joining in union to demand fair wages and decent benefits, time off to care for their family, and a regular schedule that allows them to plan for the future. Gig workers in California are leading the way and saying no more to being treated as second-class citizens, saying they deserve to be counted as full employees who are paid at least minimum wage, provided overtime pay, and unemployment insurance.

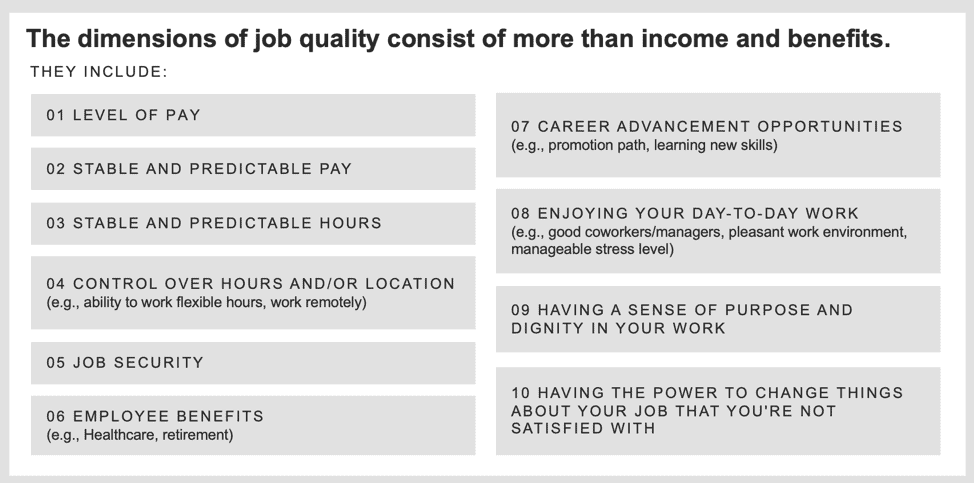

This unrest affirms our belief that the current metrics we use to track the health of jobs in America — prime among them the unemployment rate — don’t tell a complete story of our workforce. That is why Omidyar Network partnered with Gallup, Lumina Foundation, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to ask 6,600 working Americans about the quality of their jobs in the first-ever Great Jobs Survey. This survey provides a new job quality index that goes beyond wages and benefits, letting working people themselves define what makes for a good versus a bad job across 10 dimensions of job quality.

The results — released today — are sobering. We find that less than half of working people in the United States are in good jobs (40 percent), while 1 in 6 are in bad jobs. And job quality doesn’t seem to be moving in the right direction: Despite our economic expansion, most people say job quality has stagnated or gotten worse on every dimension other than pay in the last five years.

The American workforce has been going through dramatic changes in recent decades, changes that cannot be understood by looking at the unemployment rate. There are enough jobs to keep the unemployment rate low, but there’s a serious question of whether these jobs are good jobs. As the cost-of-living increases rapidly, wages aren’t keeping pace. Employers are providing fewer benefits and making it difficult for people to have predictable schedules. Global trade and automation are also disrupting the workplace, trends that are not only leading to severe disruption (including 5 million lost manufacturing jobs since 2000), but likely also a greater schism between high- and low-wage jobs, coupled with the hollowing out of the middle class.

People of color are feeling these changes even more acutely, holding them even further back from achieving equity in the workplace. Black working people are twice as likely to be in bad jobs vs. white working people (25 percent vs. 13 percent). These disparities are even more pronounced for black women: Nearly a third (31 percent) of black women are in bad jobs, compared to only 11 percent of white women.

People who are paid low wages are also struggling relative to those that are paid high wages: Just 28 percent of working people with incomes in the bottom one-fifth of all US workers (<$24,000 per year) are in good jobs, compared to 63 percent of working people in the top one-tenth of incomes (>$143,000 per year). People who are paid low wages are also much less likely to be satisfied with all dimensions of job quality. Thus, income inequality is translating into experiences that reach far beyond income, from benefits to pay stability to the dignity associated with having a good job.

People with incomes in the bottom 20 percent are also more likely to be “disappointed” with all aspects of their job, meaning there are major gaps between the importance they give to a dimension of job quality and how satisfied they are with that dimension. For example, half of this group rates benefits as highly important but are not satisfied with them in their current job (versus just 10 percent of people with incomes in the top 10 percent being disappointed with their benefits).

We also found surprising similarity in what people value across all income levels. While level of pay matters, is it rarely the most important thing. The loud and clear message from the survey is that people want jobs that are high quality across all dimensions: All 10 dimensions of job quality are viewed as important or extremely important by a majority of working men and women across all income groups.

Yet at the same time, working people feel limited in their ability to improve the quality of their jobs. We found that less than half of working people — 48 percent — are satisfied with their ability to change things about their job that they’re unhappy with, suggesting that many need better ways to be heard and have influence in the workplace. More worrisome, longer term trends indicate this problem could get worse. Union membership is on a long-term decline (despite a recent activity). Corporations are gaining more power as mergers and consolidation have led to a steady rise in market concentration. And large companies now commonly contract out work to smaller companies — known as workplace “fissuring” — denying the employee protections and benefits that large companies typically provide and driving a race to the bottom among contractors, which results in lower pay, fewer benefits, unsafe working conditions, and rising inequality.

The time for new metrics to better track and understand the quality of work in America is now. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that up to one-third of the US workforce will be displaced from their jobs by 2030 due to automation. Looking at the unemployment rate alone will tell us little about whether the new jobs being created are good ones. And due to the trends outlined above, there is reason to be concerned that good jobs may become scarcer in the future of work.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We have a choice to shape the future we want — we believe our country has enough wealth, innovation, and talent to provide great jobs for everyone, and we also believe that great jobs will unleash the best of our talent and productivity for the 21st century. But to get there, we need to understand what a great job is, and understand the state of job quality in America. The Great Jobs Survey will help us get there.

We hope this data will shed light on this topic, as well as on the challenges working people in America are facing when it comes to job quality. And we hope more policymakers, researchers, advocates, and others bring a greater focus to the importance of understanding and tracking job quality as we strive to create a better world for working people in America in this century.

Read the full report here.

*Workers from the Gallup Survey share perspectives on the qualities of a good job.